《雏菊》是一部由维拉·希蒂洛娃执导,Jitka Cerhová / Ivana Karbanová / Julius Albert主演的一部喜剧 / 剧情类型的电影,文章吧小编精心整理的一些观众的影评,希望对大家能有帮助。

《雏菊》影评(一):电影应该就是这样的

首先想起疙瘩额的女人就是女人,同样的喜剧,同样的感觉,表达不同却使得同样的理念合二为一。

我们所讨论的电影理应是一场画面的表达,不应该是控诉或者说教,玉溪的电影里面又一段导演台词大概是这样的,我所拍的电影是没有主题得,为什么电影需要一个主题?我希望我的观众每次看我的电影都有不同的领悟与感受,我所做的就是拍一部我想拍的电影。

这部电影恰好可以成为它的雏型,却整整早了半个世纪,里面的女孩子那麽可爱,胡作非为,当然这只不过是以我们的根深蒂固的道德准则为基础,这也是悲哀的,甚至我们可以想象你才说从估一切价值时候的样子,大概尼采内心就存在这这样的少女两个吧。试想当我们所有人都和少女一样,社会显然已经会无序直至死亡,也不怪马克思说有人的地方就有阶级存在,本身我们的世界就是充满了矛盾与行而上学,这都是不可避免的,导演早早就已经认识到这个浅显的道理,困难的是如何表达,激进,自由这并不是全部,导演嗨告诉我们这里面同样充满灰暗的一面,人之初未必性本善,我们的世界已经很糟糕,我们是不是应该去挽留??一切都是问题。

这些影像中的种种足以表达。

《雏菊》影评(二):意识流的荒诞片段

其实电影中的两个人女主,不能算是人,影片在多个细节都暗示:片头机器人一般的动作,上班的工人们无视他们的存在,农场里的农场主还有花园的园丁也没有发现她们。她们应该是一股超现实的欲望的意识流,情绪的意识流。影片中机械的背景音乐,时钟的背景声音,给人空间和时间错乱之感。宛如酒醉后,通过玻璃酒杯观察这个光怪陆离的世界,谵妄而迷茫。

导演不断通过两个女孩浪费和践踏食物,如饕餮凶兽,表达一种堕落,诚如影片两个女孩所说,只想更坏一点。影片的堕落仍停留在物质和生理层面,而穿插的蒙太奇画面,犹如物质土壤里想精神世界萌发的藤蔓,荒诞而有趣

可圈可点的是电影的画面表现手法。恰到好处的蒙太奇。神作一般的火车轨道。极度浪费胶片的“互剪”的碎片画面。

《雏菊》影评(三):意识流的荒诞片段

1966年的捷克斯洛伐克电影雏菊,影片前卫大胆,涉及太多标签:无政府主义,超现实,存在主义,先锋性,放在当前社会,也是让人眼前一亮的奇葩作品。其实电影中的两个女主,不能算是人,影片在多个细节都暗示:片头机器人一般的动作,上班的工人们无视他们的存在,农场里的农场主还有花园的园丁也没有发现她们。她们应该是一股超现实的欲望的意识流,情绪的意识流。影片中机械的背景音乐,时钟的背景声音,给人空间和时间错乱之感。宛如酒醉后,通过玻璃酒杯观察这个光怪陆离的世界,谵妄而迷茫。

导演不断通过两个女孩浪费和践踏食物,如饕餮凶兽,表达一种堕落,诚如影片两个女孩所说,只想更坏一点。影片的堕落仍停留在物质和生理层面,而穿插的蒙太奇画面,犹如物质土壤里想精神世界萌发的藤蔓,荒诞而有趣。

可圈可点的是电影的画面表现手法。恰到好处的蒙太奇。神作一般的火车轨道。极度浪费胶片的“互剪”的碎片画面。

《雏菊》影评(四):一部像抽象画的电影,描绘了迷惘混乱的青春。

看这部电影的时候,一开始完全不知导演在讲什么,甚至一度想关掉不看了。

但看着看着,就发觉,导演触摸到了一些自己深层的感受。

就像看一幅抽象画,乍看,觉得乱七八糟,但若细细品味,就会有一些自己的想法与感受,且每个人的想法都各不相同,每个人的想法都和自己的切身经历相关。

这部电影,让我,想到了,自己“堕落”的曾经。

或许正如片名,雏菊,每个人在年轻时,或许都会有这么一段经历。

因为不知人生为何,所以,陷入迷茫。

因为年轻,所以,不计后果。

继而,“堕落”,继而,陷入“堕落”的泥潭,继而,一味的“堕落”。

影片中,姐妹俩和老头子胡搭,胡吃海喝,肆意妄为,玩弄小伙子们的感情,把一桌宴席搞得乱七八糟……所有的所有,都是为了排解苦闷与无趣,为了让生活不那么无聊,不那么寂寞。这也是为了证明自己活着,证明自己是存在于这个世界上的。电影里,姐妹俩最怕的事,就是,自己实际是不存在的,也害怕,自己会消失在空气里。

“堕落”就像是泥潭,陷进去了就很难拔出来。欲望一时得到了满足,就会有更多更迫切的欲望等着被满足。 “堕落”一旦开始,就必然以堕落到无可救药为终点。

这一切都像是个胡闹的梦,但梦终有醒的一天。正如影片中,姐妹俩终于“扑通”一声掉到了水里,拼命地呼喊着救命,求别人救救陷入“堕落”的她们。

梦醒后,总会悔恨之前的胡作非为,所以,就会尽一切可能去弥补,可惜所谓的弥补都只是心理安慰,无济于事。就像电影里,把打破的盘子拼回去,把糟蹋了的饭菜重新放回盘子里。

那么,导演是怎么看待这些“堕落”的雏菊?在我看来,一半是同情,一半是理解。同情雏菊的无法自拔,理解雏菊一味“堕落”的心态。影片的最后,导演安排女主角一个劲儿地问:“我们很高兴对吧?” 确实,人生那么短暂,转瞬即逝,只要确确实实高兴,那就是好的。

电影也是一面镜子,每个看电影的人在电影里看到的往往是自己的倒影。这部电影里,我看到了自己“堕落”的曾经。而之所以“堕落”一词加了引号也是因为,自己觉得,人生没有所谓“对”与“错”,没有所谓的“堕落”与“积极”。就像给了每个人一张白纸,自己想怎么画就怎么画,工整是一种画风,混乱是另一种画风。人生没有标准答案。也像拍电影,严谨的叙事是一种风格,像希季洛娃一样的混乱也是一种风格。 不管是什么样的风格,只要看着心里喜欢,就是好的风格。不管什么样的人生,只要自己过得舒坦,就是好的人生。

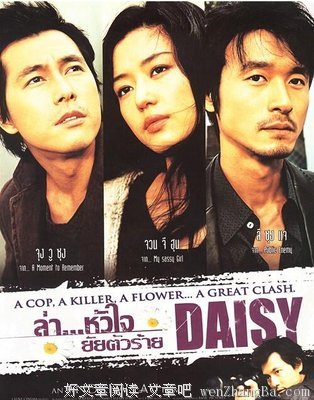

《雏菊》影评(五):触摸不到的爱情

第一次觉得一部影片竟然可以如此矛盾,不管是从剧情、人物、还是场景来看,都让人感觉冲突无处不在。 影片中的场景一开始便就是纯粹的,漫山遍野的雏菊以及青绿的小草,洁白的、淡黄的交织在一起,无形中让人有一种美的沉淀。一条小溪静静的流淌着,岸边青翠的草随着风细细飘扬,风声中传来低鸣。湛蓝的天空映衬着洁白无瑕的白云,一切都是那么美好,清新干净,连带着似乎人的灵魂都被洗涤着,而女主角就在这样的一片美景中写生,让人觉得似乎连她也纯净的不可亵渎一般。事实上,在杀手的眼里,当他模仿女主角所做的一切时,就感觉自己的灵魂也似乎纯净了一般。 虽然影片中欢快、明朗的场景较多,但也不可忽视影片本身的悲剧性。当杀手与刑警第一次枪与枪之间的对决结束时,连天都是灰蒙蒙的,低沉的音乐声,飘落的树叶以及一切让人伤感的元素交织在那个灰色的空间里,一瞬间的定格却倒映出无尽的悲伤,无穷的压抑之感袭来,我无法不感慨这部影片聚集了欢快可同时又让人悲伤的无法自拔,如此鲜明的场景对立。让人看不透她的结局。 很俗的一个剧情,杀手与刑警同时爱上一个女生,可

是它的过程却让人铭记。 女主角的画始终带着一种勃蓬的力量,向上发展,充满朝气、活力,仿佛盛开在大地之间的阳光,这一切都与杀手的世界相斥,杀手是永远无法光明正大的走在阳光下的,他是见不得光的,所以当他遇到一个阳光下的女孩时,他只能用他自己的方式去爱她。送雏菊给她,为她架桥,甚至因为她而爱上看梵高的画,为她做一切说不出的事,漠漠关注她的一切,除了不敢出现在她面前,即使装作陌生人故意擦肩而过也是幸福的。他爱的卑微,爱的沉重,爱的无法自拔。 可是这一切都被刑警的出现打破了…… 买雏菊只是一次意外,让女主角画肖像也只是为了掩护自己,最意外的是那盆被留在女主角那里的雏菊,让女主角误认为一直以来送花的人是他。此后的接近也只是为了任务,可是尽管这样,女主角还是爱上了他,那个刑警。刑警不像杀手那样爱的毫无杂致,一开始他便是怀有目的的,更遑论他的欺骗,尽管杀手的手上沾满了鲜血,可是他对女主人公的爱是纯粹的,只是因为爱而去爱,甚至在最后,为了安慰受伤的女主角,杀手不惜将自己的一切暴露在阳光中…..而刑警呢,因为一次枪战让女主角永远失去了声音,便再也无法面对她,这样的爱,实在让人伤心…… 故事的结局是惨烈的,女主角知道了一切,却还是为杀手挡了一枪,到最后,只剩下杀手一个人,他依旧是孤独的.

三个人的世界,到最后只留下了一个人的忧伤.那染了血的雏菊依旧夺目,只是心不可抑制的疼了起来……

我是说,如果你想拍一部电影给那些精神世界混乱的人,那么你有一万种办法达成目的。显然,这不是我最喜欢的那一种。。。也许我不是一个精神世界混乱的人,也许我只是一厢情愿的误会了这部电影。总有一些电影不是为了让你产生共鸣而拍摄的。。。

但是在形式上,这部电影却体现了更多的价值,我还是会惊叹于那些超现实的画面,匪夷所思的拼接以及整部影片呈现出的浮夸效果。。。有时,我们只是想看看还有没有更多的表达方式,就像是换一个视野去看待这个世界。去探索隐藏在规则背后的另一面。。。

如果摆脱了固定的电影审美模式,那么这是一部很酷的电影。。你知道在那个被革命和浪潮席卷的六十年代,我们才能看到这样的电影。。。

《雏菊》影评(七):獻給精神生活完全混亂的人

我始終覺得一部大師級的電影少不了各種看不懂,於是你就做功課,直到你恍然大悟。當然有人要個人主義,愛誰誰去,我都不懂了還看看看且不是自虐!但是不同的是,一部沒B裝B的電影和有B可裝的電影是不一樣的,所謂大師,就是有B了。既然有了B,咱就謙虛一點好了^_^

今天看的是捷克的新浪潮幹將齊蒂諾娃之《雛菊》,講述的是兩個空虛放縱的年輕女子和她們怪異舉止的片段式的、令人眼花繚亂的的超現實主義描寫。73分鐘的先鋒實驗片,開啟了捷克新浪潮的大門,但是影片完成后據說因為“浪費食物”的緣由被社會主義當局禁映直到第二年解禁并在世界範圍內獲得好評。

電影是沒有常識思維的,一堆亂七八糟的炫麗圖片,沒有劇情,穿著除了領口哪兒都一樣衣服的兩個吃貨,各種驚世駭俗。哪怕是拿到四十多年后的今天來看,依舊不失其先鋒性。

我看到了波普。色彩,底片被染上多種顏色,隨意的剪切拼圖。藍裙子倚著綠大門或者綠裙子倚上藍大門。蝴蝶三點比基尼,自創抹胸,廢棄的鋼絲卷放到頭上就是一頂帽子,鏽跡斑斑的鐵絲網穿到了身上,還有舊報紙做成的衣服。那時候andy·warhol的《瑪麗蓮·夢露》還沒出世呢。

還有女權。男人在電話里傾訴衷腸,門外敲門說愛,兩個女傻丫卻在房間里剪香腸、雞蛋、香蕉吃。車站餐廳里各種各樣瞄準她們下半身的中年男子,卻只落得一個為兩個吃貨買單換來車站一惜別待遇。

蒙太奇。新浪潮也不是只有長盡頭。恰到好處的蒙太奇(當然是你所意想不到的)依然是叫人折服的。神作的火車軌道,伴隨始終的機械動作,各種畫外音,滴滴答滴的時鐘聲。

當然,整個片子,其實是達達。兩隻性感的怪仔妹發表宣言“既然世界已經如此糟糕,我們何不讓它變得更壞”!於是搞破壞、戲弄別人、糟蹋食物、肆無忌憚,笑的卻跟邪惡的小綿羊似地。適時的插入炮彈爆裂,飛機轟炸的場景,一切規矩都打破,所有的存在都要顛覆去?毀滅,被毀滅,荒誕和虛無。怪不得布拉格之春被老大哥鎮壓后,導演被禁拍好幾年電影。

影片結尾,導演說“這部電影先給驚聲生活完全混亂的人。”

哈,精神上的快樂才是永久快樂的唯一保障。

笑死了。然後,好餓~~

“这部电影,献给精神生活完全混乱的人”

1)Formally creative:

“意识流”

情绪化音效;

时间随人物的意识流逝;

图像随着人物意识呈现;

镜头随联想逻辑剪切。

“快节奏”:情节;画面风格

2)Character: 可爱又迷人的反派

-Hedonist: 漠然不耐烦,任性放肆,充满胃口 spoiled

-重度表演型人格;角色扮演,两个人的盛宴

-两个人疯狂,一个人寂寞

3) Concept/Ideology:我们是否存在?

-世界是玩偶的舞台,是破坏女王的乌托邦

-Demoralized

-生活被剪成碎片,走向虚无

-最随喜欢的场景是床上吃东西的一段与牛奶浴的一段:渺小与壮大,焚毁与青春,食物与爱,wasted与真诚,珍惜与挥霍,一切都随便。

《雏菊》影评(九):转载366 weird movies

Imagine, for a moment, that you’re a censor in Communist Czechoslovakia in 1966, and you’re assigned the task of reviewing Daisies. The script was approved before production began, but something about the finished product looks… off. Weird. Subversive, dangerous in a way you can’t quite put your finger on. It seems oddly like something a long-haired Yankee running-dog capitalist might have dreamed up while listening to “Rubber Soul” and puffing on a doobie. The film features two beautiful young Czech girls remorselessly running mad, drinking, feasting, and taking advantage of men. It’s got random tinting, collages of wildflowers and butterflies, and experimental sequences in bright tie-dye colors scored to mock-patriotic music. There is no comprehensible plot. You’re supposed to be liberalizing censorship of the arts, but Daisies goes too far, in some way you can’t quite put your finger on. You know you’ll be drummed out of the party if you can’t come up with a reason to ban this surrealist atrocity. What do you do?

Compounding your problem is the fact that its director insists that the film is a satirical morality play, and the audience is expected to feel disgust towards the two comically decadent dolls who get their comeuppance at the end. The script makes clear the twin Maries are explicitly evil; deliberately “spoiled,” as they say. Several times in the story they stress that they are unemployed, indolent; they are a recognizable kind of Communist stock villain called the “parasite.” They live only to eat, giving nothing to society and draining its resources. Their idleness combined with their consumerist, capitalistic desires lead them to a lifestyle of scamming the establishment, consuming massive amounts of food at lavish spreads paid for by older men to whom they give nothing in return except for a one-way train ticket to parts unknown. They show no ambition greater than landing a bourgeois sugar daddy. After an hour of random leisure, they are stunned when they spy on a farmer watering his field; they literally can’t comprehend the value of a hard day’s work. They don’t understand why neither he nor the workers peddling to their jobs on their bicycles can see them, and they begin to question whether they are really happy being invisible parasites living outside of society. After childishly destroying a banquet in a final burst of immaturity, they end up cast into a lake, vainly trying to tread water, begging for forgiveness from society for their spoiled behavior. Now clad sensibly in newspapers and twine as opposed to the flowered frocks they favored in their childish days, they are allowed to return and clean up their mess to make amends for their parasitism. Perhaps, as the director claims, the film is intended as a pro-socialist indictment of indolent youth and an incitement to workerly virtue. Why then does Daisies feel so subversive?

If Daisies’ nods to socialist morality suggest you can’t ban it based on its counter-revolutionary politics, perhaps you can get it on obscenity charges. This is 1966, after all, and there’s a lot of fulsome female flesh on display here, even if it’s covered up by strategically placed butterfly display cases. True, there’s no actual sex, but that in itself presents a problem: the Maries are not only non-productive members of society, they’re also non-reproductive members of society. They have no use for men and are exclusively involved with each other. The girls dress up in nighties and wrestle, Marie II lightly canes Marie I on the derriere as she looks out a window, they hold hands and pet, and take baths together in milk. At one point, Marie I pokes Marie II lightly in her bare lower abdomen with a fork and says “I don’t see any other meat here.” Despite the fact that they’re only interested in hanging out together, they plow through a succession of men and delight in hinting of sexual adventures they have no intentions of embarking on. In the famous butterfly sequence, it’s Marie II who strips for her lepidopterist Lothario of her own accord. She then demurs “I don’t know what you’re talking about” when he protests his love for his demure nude girl, before asking “isn’t there some food around here?” Later, when he calls her on the phone to further declaim his passion, she and Marie I lie there listening in their underwear, giggling and slicing up various sausages, pickles and bananas that they happen to have lying around the flat with a pair of scissors.

If you’re a Czechoslovakian censor in 1966 chances are good you’re a male, and you might not want to hint at how uncomfortable that scene of the Maries cutting phallic fruit into tiny slices and feeding it to each other makes you feel. So, if you’re not going to ban the film on the basis of its politics and you’re not going to ax it for sex, what’s left? According to legend, at least, the real-life Czech censors came up with an ingenious justification that allowed them to save face without looking at all ridiculous—they banned Daisies for food wastage. If your planned economy isn’t bringing in the abundant harvests you hoped for, you don’t want moviegoers reminded of how hungry they are by watching two impudent dames rolling around in a bed of apples, casually snipping sausages or ordering a whole chicken as the final entrée of a four course meal. Daisies’ climactic food fight was the sour cherry on top of this too-decadent sundae. After the girls have fingered the finger food and pawed the pâté at someone else’s banquet, they grab giant handfuls of creamy cake and fling them onto each others’ faces, ending their party by stripping to their slips and walking all over the remaining uneaten feast in their high heels in an impromptu fashion show. The movie itself realizes that with this gluttonous display the Maries have gone too far; it uses its magical powers of retribution to plunge the girls into a cold lake after they hang on the chandelier. But the damage has already been done. The edible orgy may be a satirical assault on Western style capitalistic decadence, sure, but girls playing with their food is something too unvirtuous to tolerate.

If she’s telling the truth, then Vera Chytilová may have begun filming Daisies with an honest intention of critiquing the nihilism of these youths; but along the way she was seduced by the total artistic freedom she allowed herself. Watching the film today, everyone sides with the Maries rather than despises them. Their gleeful destruction and playful reconstruction of their drab world inspires us. At one point in the film, they cut off each others’ arms and heads with scissors; rather than getting upset about it, Maire I crosses her eyes and sticks out her tongue, Marie II bumps her decapitated head up against her longtime companion’s, and the two torsos duel with scissors until they’ve cut the very film we’re watching into shards that dance around on the screen independently. The freedom that we respond to in Daisies doesn’t actually come from the silly Maries and their vandalism of a banquet; it comes from watching the filmmakers demolish the rules of cinema. That’s the unfettered, truly subversive intellectual freedom that the censors sensed and felt compelled to repress. Surrealism, which depends on the free associative play of the mind, implicitly critiques rationalism and order—all order, and therefore specifically whatever order is reigning at the time. The same weapons the avant-garde used in Western Europe to attack capitalism inevitably eviscerated Marxism when used on the other side of the Iron Curtain. (That’s one of the reasons Western leftists didn’t universally embrace Daisies; Jean-Luc Godard weakly protested that the movie was “apolitical and cartoonish”).

In a bit of prescient irony, Chytilová intuited what would get Daisies banned in the film’s final dedication. Over footage of bombed out buildings and cued to the sound of gunfire, the following words type themselves out: “this film is dedicated to those who get upset only over a stomped-upon bed of lettuce.” Daisies stomped upon enough lettuce to get itself suppressed, but the regime that banned it had a lot more to be upset about.

《雏菊》影评(十):“我们存在吗?”

为什么这儿有水?

为什么这儿有条河?

为什么我们觉得冷?

我们存在吗?

你们当然不存在,你们当然存在。

于是她们爬到铺着厚床垫的床上,把一盒子的剪刀倒出来,剪下对方的胳膊,剪下对方的脑袋,把对方剪成碎片。

她们当然不是真实的人类,连她们自己也清楚地知道这一点。活动时咯吱作响的身体,做作的说话方式,她们是按照人们想象中的少女形象制造出的影像。天真、狡猾、孩子气、残忍、甜美、无所顾忌,各种要素放入事先准备好的可爱躯壳,然后让她们把盖着厚厚奶油的蛋糕往嘴里塞。

她们知道自己不存在,可她们又是存在的。于是,游戏只是为了游戏,胡闹只是为了胡闹,闪动的画面只是为了闪动的画面。变坏只是一个借口,它是游戏的一部分。而游戏只是游戏,所有的有趣来源于无趣。你指望电影里的一个虚构角色怎么样?这样很有趣,但是我们根本不在乎。

吊灯掉下来了,她们不是活生生的人,有什么关系,一切重新开始。游戏只是为了游戏,胡闹只是为了胡闹,闪动的画面只是为了闪动的画面。

这样很有趣,但是我们根本不在乎。

…………………………