《莎士比亚十四行诗集》是一本由(英)莎士比亚著作,北京大学出版社出版的338图书,本书定价:16.50元,页数:1998-09-01,特精心从网络上整理的一些读者的读后感,希望对大家能有帮助。

《莎士比亚十四行诗集》精选点评:

●读完这个之后,我有一段时期都觉得自己是个情圣……

●莎士比亚才是最高级的催婚

●很久

●妖怪用的切口。

●本来想读英文版的,却被古英语的“thee”、“thuo”等等这些东西吓退了。(对不起我是学渣我悔罪) 维多利亚时代的风格,浓丽馥郁呼号。有些比喻很妙。

●断断续续读了3年

●通常真正的文学巨匠都是可以如意把弄文字的,很轻巧却一点也不给人一种厚重烦腻感。

●慢慢看,我对诗歌感受力有限,主要是长见识的

●一字千斤重 不得了~

●审美疲劳

《莎士比亚十四行诗集》读后感(一):总觉得读译文时很拗口

感觉译者太尊重原作的结构了,以至于译文读起来时很拗口。

虽然我自己以往翻译材料时也喜欢这样,但是文学著作如果过于死板了,其灵魂就没有掉了。

阅读诗歌时,我还是喜欢读出声来,去感觉画面。

这本诗集的译文在传递映像思维方面,也许还能提高吧。

为此买了新版的莎士比亚全集,还没到,不知道其中的翻译如何。

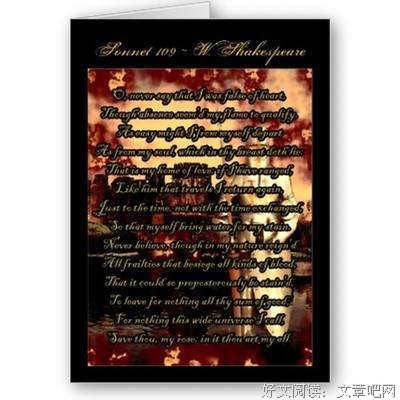

《莎士比亚十四行诗集》读后感(二):Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

感觉诗还是要读原文的好, 翻译的诗感觉总是味道不对,比如第十八首

hall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date.

ometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

y chance or nature's changing course untrimm'd;

ut thy eternal summer shall not fade

or lose possession of that fair thou ow'st;

or shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st:

o long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

o long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

能否把你比作夏日璀璨?

你却比炎夏更可爱温存;

狂风摧残五月花蕊娇妍,

夏天匆匆离去毫不停顿。

苍天明眸有时过于灼热,

金色脸容往往蒙上阴翳;

一切优美形象不免褪色,

偶然摧折或自然地老去。

而你如仲夏繁茂不凋谢,

秀雅风姿将永远翩翩;

死神无法逼你气息奄奄,

你将永生于不朽诗篇。

只要人能呼吸眼不盲,

这诗和你将千秋流芳。

《莎士比亚十四行诗集》读后感(三):沉睡之镜。

沉睡之镜。

越过了溪谷和山陵,穿过了荆棘和丛黍;

越过了围场和园庭,穿过了激流和爝火;

我在各地漂游流浪,轻快得像是月亮光。

-----------W.William Shakespeare

把梦想打开,把世界关闭。

嶙峋的森林里,栖息着沉睡的彩虹。

我在多少年里茫然的穿过呼啸的风岭,混沌的沉睡着。

记忆中同样逼仄的水氲反复出现在梦镜里,

在黑白森林里沉睡着的天空冥器,

被光洁的水光折射出温暖而冷漠的光。

跃动的梦想。

日本建筑师安藤忠雄曾说,只有通过用身体的直接触摸,才能从木质上感知建筑。

而是不是时洪中你我矫捷的追随与被时光割裂的感知也是这样呢。

站在世界尽头我试图眺望梦境里反复出现的流光境域,

却只是漫天的白雪漾洒,风吹四季。

每一时每一刻,同时接受这来自它们的辛苦馈赠。

从固定的位置看向天,眼眶便迅速的潮湿起来,滴落在雪地里,有尘埃的破碎声.

从静致安好的春熙走来,却不再留恋隐衬下的心情如何回归。

在通往圣殿的路途中,无数的勇者披荆斩棘,彼此厮杀的抢路。

大家慢不作声的赶路,在困顿和失落中举步维艰,内心慢性糜烂。

越来越悲伤越来越冷漠,变得平稳却又叛逆。

点燃焦躁的导火索需要的火星埋藏在内心里,岌岌可危的起伏。

想要找寻那一点微弱的火光,却不料走进了更深的黑暗。

Lily.L说:梦想是个天真的词,但实现梦想更是一个残酷的词。

这两个词是从来都不能对等的词。

其中却也有可以肯定地预示,无论向前的道路上风景如何,

但你所走的每一步,都会比上一次的步履更接近遥望的星辰。

尽管这个不理想的世界充满了尖锐和讽刺,

也要忍受实现给予我们的幸福和苦难,无聊或者平庸。

“为什么丑恶的事情总在身边,而美好的事情却远在海角。”

奎扩的黑色水面波纹抖擞出你我的世界,那是明日以前的美好星光。

伸手便可触及。

昨日的梦境中,我远远的站在山峦高处眺望远处渺茫的湖岸。

夜幕苍茫,芦苇在夏风中渐次倒伏。

雁群掠过,有弧线的忧郁反复穿越。

沉睡之镜的芒泽照在我的面庞之上,

重现不再是我容颜。

你曾说路途上的遭遇只是通向圣殿中的庞贝呼啸。

所以我一直都相信你。

我再醒来时告诉自己:

不要为了一时的黑暗,而错过了一地春熙梨花的美丽阴影。

《莎士比亚十四行诗集》读后感(四):走进莎士比亚的商籁世界

读了莎士比亚的十四行诗,才知道它们被誉为西方诗歌中不朽的瑰宝绝非徒有虚名。

莎士比亚写了154首十四行诗,但涉及的主题并不多,我把它们归为两大类,即美和爱。莎翁反复热情讴歌这两大主题,他对美和爱的敏感程度令我惊讶。

莎翁热爱和珍惜一切美好的事物,并为美随着时光流逝而痛惜不已。他希望美能够永存,提出了两个解决之道:繁衍后代和创作诗篇。在前17首诗中,他反复劝告美貌的朋友赶快结婚,抚养后代,让美貌在孩子身上得到传承,而不要“人去貌成空”。用这种理由劝人生儿育女的还真没有第二个,更何况写了17首诗说这个道理,可见莎翁对美是何等珍视。

“我能否把你比作夏日”恐怕是他的十四行诗中最脍炙人口的一首,这首诗就表达了美在诗歌中得到永生的思想。莎翁的很多诗都一边热烈歌颂爱友的美,一边为青春易逝、红颜易老而无限痛心:“唉,不由我心焦,未来的世代听我忠告:/你们还未出世,美的夏天已死在今朝。”值得欣慰的是他可以借墨迹“显圣通灵”,“有我诗卷,我爱人便韶华长驻永不凋”。比起中国古诗中常见的伤春悲秋的作品,莎翁用诗使美永存的思想确实更为积极,中西文化的差异由此可见一斑。

莎诗中那种压倒一切的爱的激情更是震撼人心。只要有爱,他就可以藐视功名,忘记烦忧:“但记住你柔情招来财无限,/纵帝王屈尊就我,不与换江山。”拿起笔来,他写出的全是爱的心声:“天上太阳,日日轮回新成旧;/铭心之爱,不尽衷肠诉无休。”与爱人分离的时候,他感到周围的一切都失去了光彩,连小鸟都不再歌唱,“它们即使启口,也吐出声声哀怨,/使绿叶疑隆冬将至,愁色罩苍颜。”想到自己来日无多,他无私地劝爱人在自己死后不要伤心,免得被别人当作取笑的把柄。这些诗句所表达的真挚深沉的爱,穿越几百年的时空仍然感人至深。

遗憾的是莎翁深情如此,他的情人却并不那么专一。她似乎很有魅力,周旋在众人之间,使莎翁妒火中烧而又奈何不得。他固然希望情人一心爱自己,但他爱她爱得几乎失去了自我,像一个忠实的奴仆,对她所做的一切听之任之,自己则忍受着巨大的痛苦折磨。他爱恨交织,只有无奈地感叹:“唉,我这植入你欲田的爱真是蠢猪,/眼见你为所欲为,却漠然视若无睹。”他本该责备情人不忠,最后却责备起自己来:“到头来,我落得沦为你的帮凶,/帮你这甜偷儿无情打劫自己的心房。”一个男子痴情至此,古今中外都可谓罕见了。当情人要与他断绝关系时,他知道无法挽留,只好说:“你乐意恨我就恨我吧,立即开始,/反正现在全世界都与我为敌。”看似洒脱,实际上内心的隐痛只有自己知道:“好一场春梦里与你情深意浓,/梦里王位在,醒觉万事空。”读到这里,真是万千惆怅只能化作一声叹息了。莎翁的这些诗让我深刻体会到一个人在深爱时可以把自己看得多么微不足道。

人间情爱,归根结底无非一个欲字。人生经历丰富的莎翁自然深知此理:“损神,耗精,愧煞了浪子风流,/都只为纵欲眠花卧柳。”然而他和世间众多风流浪子一样,明知到头来都是一场空,仍然摆脱不了贪图一时之乐的天性:“恰像是钓钩,但吞香饵,管叫你六神无主不自由。” 对人性剖析之深刻实在令人叫绝。而此诗最后两句更是振聋发聩:“普天下谁不知这般儿歹症候,/却避不得偏往这通阴曹的烟花路儿上走!”矛盾,痛苦,绝望,无奈,种种情绪交织在一起,在这两行诗中表达得淋漓尽致。读后不免掩卷深思:人就注定要做欲望的奴隶吗?这首从单纯的抒情上升到理性高度的诗,不能不说是154首十四行诗中的可圈可点之作。

读完莎士比亚的诗集,不禁深深感慨于他对人生的投入和激情,他热烈张扬的生命力。这样的人生,比起我同样喜欢的王维的闲适,苏轼的洒脱,该是另一种精彩吧。

《莎士比亚十四行诗集》读后感(五):Shakespeare Sonnet 18

hakespeare sonnet 18 begins the thematic group in which the speaker/poet muses on his writing talent, often addressing his Muse, his ability, and even his poems.

First Quatrain – “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”

In the first quatrain, the speaker muses about comparing the poem to a day in summer; then he begins to do just that. In comparison to a summer’s day, the poem is deemed “more lovely and more temperate.” The qualification of more “lovely,” at this point, seems to be just the speaker’s opinion, but to prove the poem more temperate, he explains, “Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May”: the “rough winds” that blow the young buds of flowers about is certainly not mild or temperate. And also summer just does not last very long; it has “all too short a date.”

The poem, when compared to a summer’s day, is better; its beauty and mildness do not end as summer along with its “summer’s day” does. The reader wonder why the speaker, just after claiming his intention of comparing the poem to a “summer’s day,” then first compares it to a spring day—“the darling buds of May.”

Even before summer begins, the May flowers are being tossed about by intemperate breezes; therefore, it stands to reason that if the prelude to summer has its difficulties, one can expect summer have its own unique problems that the poem, of course, will lack.

econd Quatrain – “Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines”

In the second quatrain, the speaker continues elucidating his complaints that diminish summer’s value in this comparison: sometimes the sunshine makes the temperature too hot: “Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines.” The sun often hides behind clouds, “often is his gold complexion dimm’d.” The reader can realize the implications here: that these inconvenient qualities do no plague the poem.

Then the speaker makes a generalization that everything in nature including the seasons—and he has chosen the best season, after all; he did not advantage his argument by comparing the poem to a winter day—and even people degenerates with time, either by happenstance or by processes the human mind does not comprehend or simply by the unstoppable course of nature: "And every fair from fair sometime declines, / By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimm’d.”

o far, the speaker has mused that he shall compare the poem to a summer day, and the summer day is losing: even before summer begins, the winds of May are often brutal to the young flowers; summer never lasts long; sometimes the sun is too hot and sometimes it hides behind clouds, and besides everything—even the good things—in nature diminishes in time.

Third Quatrain – “But thy eternal summer shall not fade”

In the third quatrain, the speaker declares the advantages that the poem has over the summer day: that unlike the summer day, the poem shall remain eternally; its summer will not end as the natural summer day must. Nor will the poem lose its beauty, and even death cannot claim the poem, because it will exist “in eternal lines” that the poet will continue to write, “When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.”

The Couplet – “This gives life to thee”

The couplet—“So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee”— claims that as long as someone is alive to read it, the poem will have life.

Read more: http://poetry.suite101.com/article.cfm/shakespeare_sonnet_18#ixzz0Pd5vEQeg